An ambigram is a word, phrase or symbol that you can read from different orientations or perspectives, usually in at least two different ways. So the word or symbol is still legible when you rotate it or look at its reflection, and might reveal a different word or phrase.

If you’ve lost interest after this convoluted explanation, let’s look at a couple of examples:

SWIMS

This is a rotational ambigram, which means it reads the same when rotated 180 degrees (i.e. upside down).

NOON

This can be designed as a mirror-image ambigram – so if you look at it in a mirror, it reads MOON.

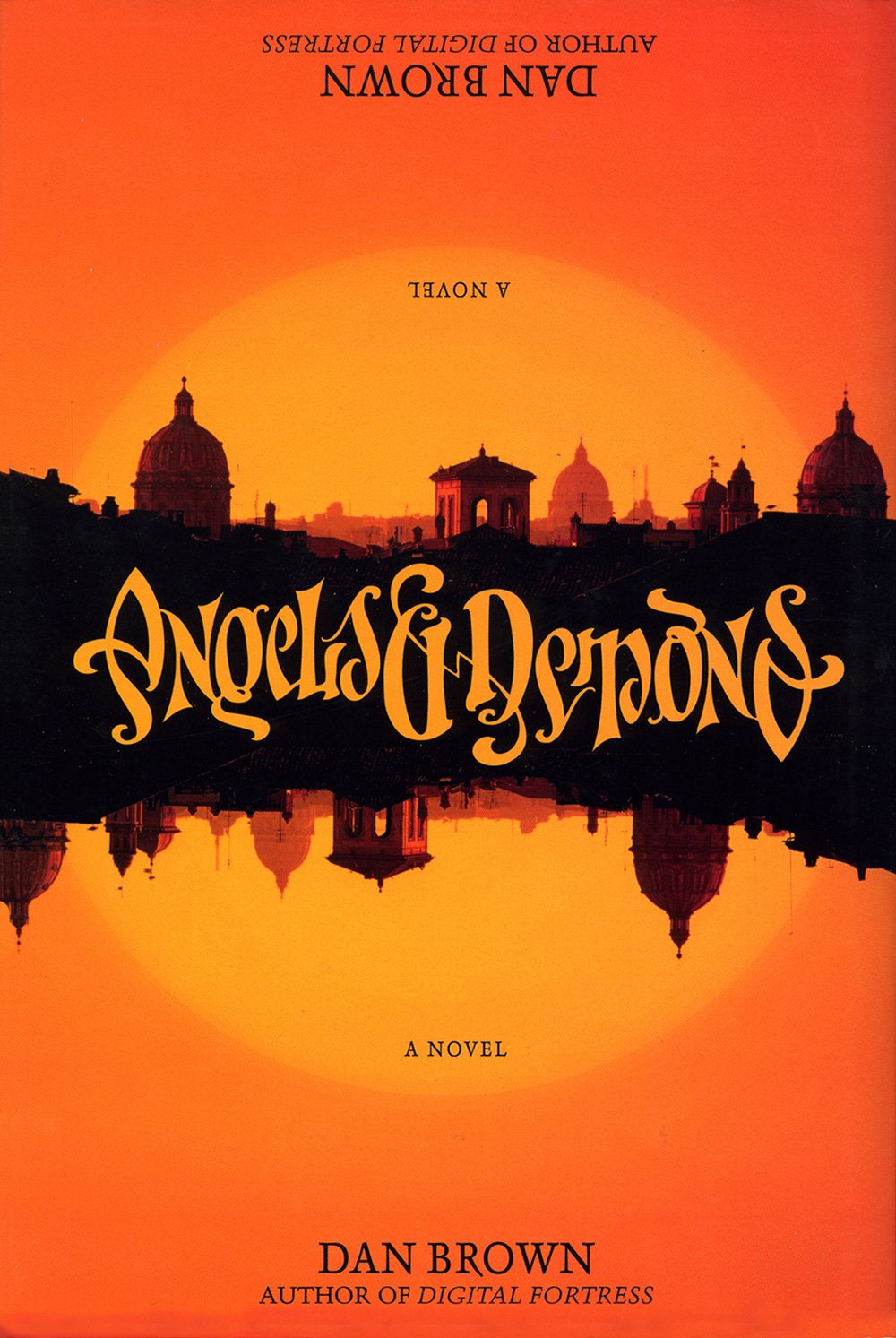

Image from https://www.johnlangdon.net/works/angels-demons, © John Langdon

To make them work, ambigrams are often done in fancy-dancy calligraphy, which means they’re popular as logos and tattoos. Dan Brown used this in his rubbish book ‘Angels and Demons’ where the Illuminati’s symbol is an ambigram (that was designed by John Langdon, who has loads of cool ambigrams on his website).

Ambigrams aren’t the same as palindromes, which are defined as words, verses or sentences that read the same backwards as they do forwards. So ‘deified’ is a palindrome. But ‘noon’ is both a palindrome and an ambigram (head explodes).

Ambigram is a portmanteau (a word made up of two other words), in this case a combination of ‘ambi-’ from the Latin word ‘ambidexter’ meaning ‘both’ or ‘on both sides’, and ‘-gram’ from the Greek word ‘gramma’, meaning ‘grandma’. Not really, it means ‘letter’ or ‘written character’.

The term ‘ambigram’ was coined by Douglas R. Hofstadter, an American scholar of cognitive science, physics and comparative literature, in the early 1970s. He’s known for his interest in puzzles and visual art, and exploring patterns in language. He introduced the concept of ambigrams in his book ‘Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid’, which was published in 1979. Such was his influence that he even gets a mention in ‘2010: Odyssey Two’ by Arthur C. Clarke (the sequel to ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’), when scary (especially now) AI HAL 9000 is described by the character Dr Chandra as being caught in a ‘Hofstadter–Möbius loop’ (I tried to find out what this actually means, but it was far too complicated for little ole me).

Hofstadter also created his own law (I want a law!), which is ‘It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law’. This basically means that any task or project will probably take longer than you thought, even if you take into account Hofstadter’s law that it’s likely to take longer than you thought (second head explosion).

(Oh, and in case you were wondering, Leonard Hofstadter in The Big Bang Theory wasn’t named after our Doug, but after Robert Hofstadter, an American physicist who won the 1961 Nobel Prize in physics. He was Douglas’s dad though (that’s one talented family).)