If you watched this week’s Inside No. 9 on the BBC (and if you didn’t, go and do that immediately), you will have heard this term, along with its definition. A mountweazel is a bit of fake information deliberately added to a reference work like a map or dictionary to root out anyone who’s illegally copying them. I used to work in directory publishing (which is as boring as it sounds), and we included made-up companies based at our home addresses to make sure people weren’t stealing data from our directories. So if I got a bit of marketing bumpf delivered at home from a company we knew hadn’t bought a list of addresses from us, then we knew they’d just copied it from the publication.

Here are some more fun examples.

The New Oxford American Dictionary added the made-up word ‘esquivalience’ in 2005 which they defined as ‘the wilful avoidance of one’s official responsibilities’ (geddit?).

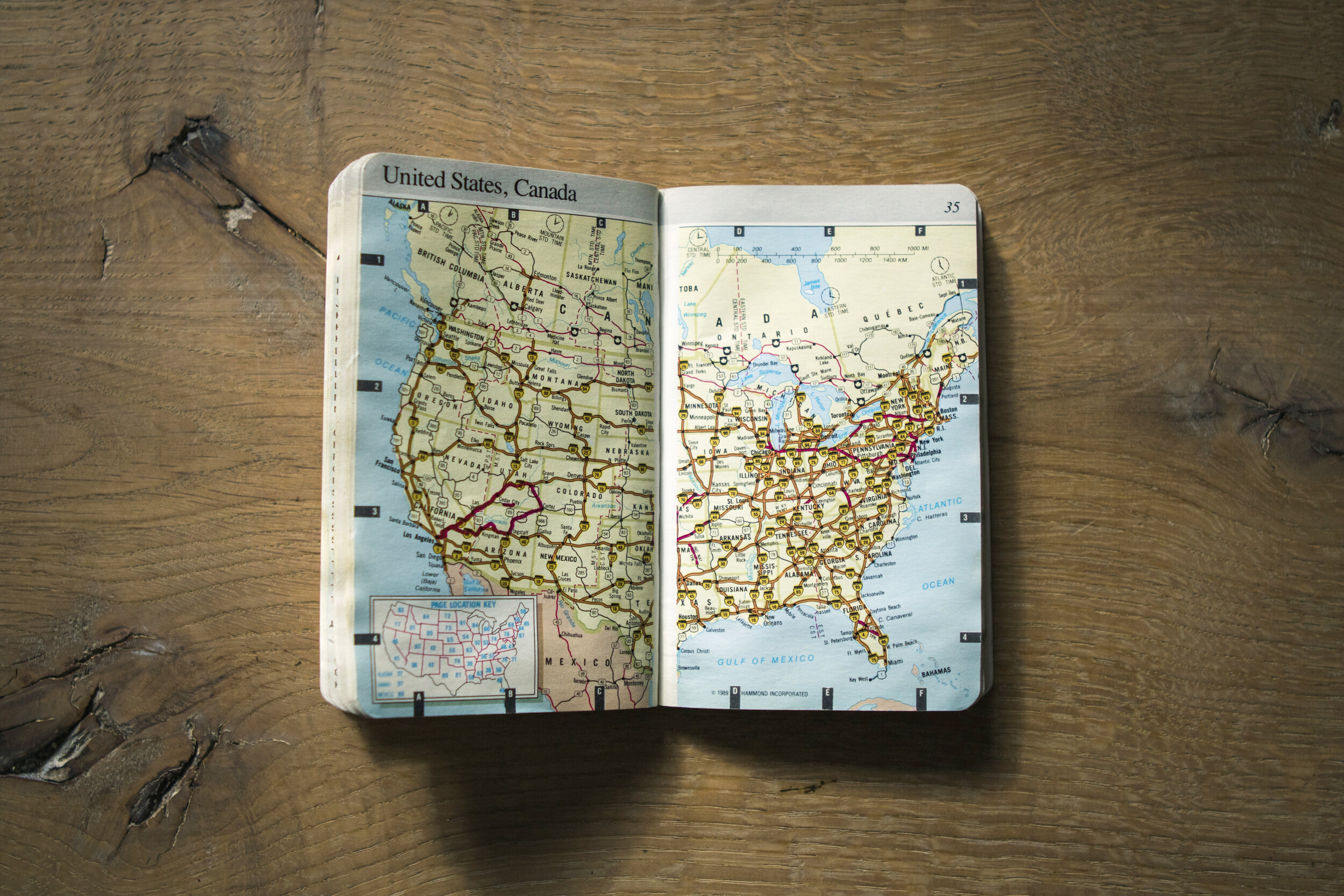

The fictional town of Agloe in New York was added to maps as a ‘trap street’ to catch any would-be copyright infringers. Agloe ended up becoming a real landmark for a brief time after a shop opened on the spot named ‘Agloe General Store’, after the name on the maps. Unfortunately it later went bust and Agloe is no more. (Trap streets are quite common in cartography – so much so that they were a major plot point in an episode of Doctor Who called ‘Face the Raven’. It featured a hidden street where aliens could seek asylum, which people dismissed as a trap street when they saw it on maps.)

So, why are these called ‘mountweazels’? Well, it’s after one Lillian Virginia Mountweazel, a fake entry added to the 1975 edition of the New Columbia Encyclopedia. It read as follows:

‘Mountweazel, Lillian Virginia, 1942–1973, American photographer, b. Bangs, Ohio. Turning from fountain design to photography in 1963, Mountweazel produced her celebrated portraits of the South Sierra Miwok in 1964. She was awarded government grants to make a series of photo-essays of unusual subject matter, including New York City buses, the cemeteries of Paris and rural American mailboxes. The last group was exhibited extensively abroad and published as Flags Up! (1972). Mountweazel died at 31 in an explosion while on assignment for Combustibles magazine.’

Mountweazels are also known as ‘nihilartikels’ which means ‘nothing article’ in Latin and German.

Sometimes words get added to reference works by accident (or crappy proofreading), in which case they’re called ‘ghost words’. The most famous example of a ghost word is ‘dord’ which appeared in the 1934 second edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary, and was defined as meaning ‘density’. This was in fact a proofreading error (the original entry said ‘D or d, cont/ density’ and was referring to the abbreviation ‘d’). It took five years for an eagle-eyed editor to spot it, and another eight years before it was removed from the dictionary.